Friday, September 30, 2011

Thursday, September 29, 2011

MY SOLUBLE SOUL IS UNFOLDING INTO TIME AND SPACE BY THE SOLAR LOVE ARKESTRA

STRAIGHT TECH-NO?-DOMINIC

Monday, September 26, 2011

PAINKILLER - FREESTYLERS FT. PENDULUM NOISIA REMIX

Saturday, September 17, 2011

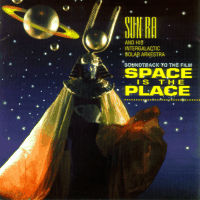

SUN RA:STRANGER FROM OUTER SPACE

by Mike Walsh

In tomorrow's world, men will not need artificial instruments such as jets and space ships. In the world of tomorrow, the new man will 'think' the place he wants to go, then his mind will take him there. -- Sun Ra, 1956

Just the same old same thing

C'mon sign up with

Outer Spaceways, Incorporated

In 1961, the Arkestra moved to Montreal briefly and, following a series of aborted gigs, then to New York. By that time, only Gilmore, Allen, and bassist Ronnie Boykins remained with the Arkestra.

Actually, the Arkestra was faced with eviction from the house it rented in the Lower East Side, so the band relocated when Marshall Allen's mother offered them a rowhouse in the Germantown section of the city. "We didn't have anywhere else to go," Gilmore said.

Actually, the Arkestra was faced with eviction from the house it rented in the Lower East Side, so the band relocated when Marshall Allen's mother offered them a rowhouse in the Germantown section of the city. "We didn't have anywhere else to go," Gilmore said.Impulse, a division of ABC, released a handful of Sun Ra LPs in the '70s. These releases gave him wide distribution and international exposure for the first time.

A place where you can be free

There's no limit to the things you can do

Your thought is free and your life is worthwhile

Space is the place

"I'm a spirit master," he said. "I've been to a zone where there is no air, no light, no sound, no life, no death, nothing. There's five billion people on this planet, all out of tune. I've got to raise their consciousness, tell them about the wonderful potential to bypass death."

"I'm a spirit master," he said. "I've been to a zone where there is no air, no light, no sound, no life, no death, nothing. There's five billion people on this planet, all out of tune. I've got to raise their consciousness, tell them about the wonderful potential to bypass death." In the late '80s and early '90s, Sun Ra did garner national recognition. The alternative rock world embraced him as a major influence. The Arkestra played a gig on Saturday Night Live and jammed in Central Park with Sonic Youth. Robert Mugge made an excellent documentary about him and his space age theology called Sun Ra, A Joyful Noise. He was honored with the Liberty Bowl award from the city of Philadelphia and was voted the top big band in a Downbeat magazine critic's poll. And for the first time, he released two recordings on a major label-A&M.

In the late '80s and early '90s, Sun Ra did garner national recognition. The alternative rock world embraced him as a major influence. The Arkestra played a gig on Saturday Night Live and jammed in Central Park with Sonic Youth. Robert Mugge made an excellent documentary about him and his space age theology called Sun Ra, A Joyful Noise. He was honored with the Liberty Bowl award from the city of Philadelphia and was voted the top big band in a Downbeat magazine critic's poll. And for the first time, he released two recordings on a major label-A&M.All of Sun Ra's music was steeped in the past but was simultaneously pioneering. He used tradition not to repeat but to take the music somewhere new. Whatever the style, his music always challenged the listener.

Many light years in space

I'll build a world of abstract dreams

And wait for you

Monday, July 4, 2011

BJORK: 'MANCHESTER IS THE PROTOTYPE'

The Icelandic singer's Biophilia project incorporates handmade instruments, iPad apps, David Attenborough's nature films and an album too – and she's showcasing it all at Manchester international festival

- Alex Needham guardian.co.uk,

Originally formulated by scientist Edward O Wilson, the biophilia hypothesis suggests that human beings have an innate affinity with the natural world – plants, animals or even the weather. Yet it's not biophilia but good old-fashioned fandom that has drawn a small band of Björk obsessives to queue outside Manchester's Campfield Market Hall since 10am this morning. Not that there's anything old-fashioned about the woman they are here to see. Biophilia is the Icelandic singer's new project – the word means "love of living things" – and promises to push the envelope so far you'll need the Hubble telescope to see it.

A collection of journalists have already had a preview at a press conference in the Museum of Science and Industry over the road. Björk is absent, preparing for tonight's live show, her first in the UK for over three years, which will open the Manchester international festival. Instead, artist and app developer Scott Snibbe, musicologist Nikki Dibben and project co-ordinator James Merry talk through Biophilia's many layers. There will be an album in September, with an app to go with each of the 10 songs. There will be an education project, designed to teach children about nature, music and technology – some local kids will embark on it next week. There will be a documentary. And then there will be tonight's show, performed in the round to a 2,000-strong crowd including journalists representing publications from New Scientist to the New York Times, as well as the diehard fans waiting outside. One, 20-year-old Nick from London, is a classical violinist who has loved Björk since the age of 14. "I wasn't really into pop at all until I heard Medúlla," he says, citing her most challenging album. "It was like a gateway drug from me liking difficult 20th-century western art music to liking pop."

It's a journey in the opposite direction from the one most music fans make, and one which speaks volumes about the complexity of Björk's work. "More classical musicians respect Björk than any other pop star," he adds.

At the museum, Snibbe is demonstrating the apps. The app that goes with the first single, Crystalline, includes a game in which you collect crystals in a tunnel, through which process you alter and customise the music. The app also includes an abstract version of the musical score; and an essay by Dibben that explains, in this case, how the structures of crystals relate to the musical structure of the song. The app for another song, Cosmogony, presents a 3D cosmos you can navigate. Each app has been created by a different – often rival – developer. "To me, it feels like the birth of opera or the birth of cinema," says Snibbe.

Yet Björk didn't have such lofty aspirations in creating the project. "My main aim is to not get too bored myself," she says, via email (she rests her voice between shows). "I feel that if I'm curious and excited there is a bigger chance the listener might be. At the end of the day, it's more about the feeling of an adventure rather than the details of the adventure itself. So in short: whatever turns you on."

That said, the change from a passive to an active listening experience is a radical one. "The apps are mostly made for headphones and a private experience," says Björk. "What you see live is only us playing our version. You can play a totally different versions at home." If you've no desire to do that, Merry is at pains to point out that Biophilia will still exist as a CD or download – and indeed only those with access to an iPad or iPhone can experience the apps. So far, the project has been too expensive to adapt to other handheld devices.

At the show venue, the journalists are being given a tour of the new instruments that have been specially built for the project. One contraption looks like a giant silver mangle decorated with two massive ear trumpets, but is called a sharpsichord. There are two giant pendulums, which have strings plucked by a plectrum as they swing past. There's a Tesla coil that descends in a cage from the ceiling; two prongs that emit purple flashes of lightning – and, with it, sound. There's also a celeste, which has been gutted and fitted with the pipes of a gamelan. These fantastical devices are controlled by an iPad. Above the performance space is a circle of screens that show the apps for each new song; moving tectonic plates for Mutual Core; invading pink cells for Virus ("Like a virus needs a body, as soft tissue feeds on blood, I will find you, the urge is here," go the lyrics).

It must be one of the most complex pop shows ever, and according to Björk, it could have been more elaborate still. "Manchester is the prototype," she says. "We had to leave many things out because of budget and time and stuff." As it is, the whole project has taken three years and cost so much money she told Rolling Stone that "we'll be lucky if we earn zero".

Yet, on purely artistic grounds, it's hard to regard Biophilia as anything other than a success. As the lights go down, Björk's childhood hero David Attenborough's unmistakable voice, recorded just that day, fills the room to explain the songs. The show includes Björk's favourite footage from BBC nature documentaries playing when she performs older songs. Hidden Place is illustrated by a beautiful but disturbing clip from Attenborough's Life – of a seal's corpse being devoured by psychedelically coloured worms and starfish. All 10 tracks from the new album are played. Such an onslaught of new material would try the patience of most audiences, but this one is rapt – no one even goes to the bar.

Much of this is due to the sensory bombardment of music, images and costumes – not least Björk's bright orange wig, which a comment on the Guardian's review says makes her resemble a tamarin monkey. Her decision to ban cameras and other recording equipment from the venue has also played its part. "I feel since everyone has made such an effort to be there all together at the same place and time, we might as well go for it," she says. "It can be hard to play music for people who are filming you for Twitter or whatever. It's like going to a restaurant with someone who keeps texting their friends while you are speaking to them – hard to concentrate."

Then there's Björk's extraordinary voice, once compared by Bono to an icepick, and still imperishable at 45. "My voice has changed," she says. "I thought it had gone a little deeper. On my last tour I got nodules [on the vocal cords] but managed to stretch it out with three years of vocal work, so I'm back to my old range now." Björk "adores" a whole range of singers: "Chaka Khan, Beyoncé, Antony" – the latter being Antony Hegarty, a former collaborator who is here in the audience – though her "favourite singer alive today" is Azerbaijani devotional singer Alim Qasimov. She is accompanied by a 24-piece Icelandic choir she discovered on YouTube.

After spending so long meticulously making Biophilia, performance feels liberating. Live shows and making an album are, says Björk, "extreme opposites. After noodling for ever on an album, gathering together the best moments, it's refreshing and healthy to have to do it all in one whack. Then you sort of have to take real life into it and accept that you only have whatever you have that day – and that is enough."

Right now Björk is at the intersection of music, nature and technology, exploring how the three together might help build a more sustainable future. But is it still pop? "Yes, absolutely!" Björk claims. (Dibben, who wrote a book about Björk, says the singer is wary of having her music hived off into the rarified world of the academy.) "Or perhaps I would rather call it folk music – folk music of our time. I was never too much into Warhol and the whole pop thing – it felt a bit superficial. I prefer folk. People. Humans."

• Bjork plays Manchester international festival on 7, 10, 13 and 16 July. Biophilia is released in September

- guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011